Review of “Final Solution The Fate of the Jews, 1933–49” — Part One of Five

Faced with Jewish exaggeration, we exaggerated our response to it. And this

response is becoming dominant. When Microsoft’s Artificial Intelligence “chatbot”

recently made its appearance online, intended to reflect trends in contemporary

internet discourse, it very

quickly announced that “Hitler was right” and called for a race

war. The Guardian reported after the incident that the “bedrock“

of modern “anti-Semitism” was “offensive humor, irony and

moral relativism.”

Some of the key weapons of the Left have been hijacked.

Epitomizing these trends are two important alt-right productions founded by

young activists, The

Daily Stormer (founded by 31-year-old

Andrew Anglin [

Hated by the Wiki ]) and Mike

Enoch's The Right Stuff.

Jon Stewart's

Daily Show

now finds a rejoinder in The Right Stuff’s mocking “Daily Shoah”

podcast. [ Jon Stewart

aka Jon Stewart

Leibowitz is, naturally enough a Jew - Editor ] Stretching even further is Anglin’s over-the-top,

provocative-to-the-max Daily Stormer, which features intentionally

extreme, tongue-in-cheek headlines penned by young writers employing monikers

like “Grandpa Lampshade.” Breaking taboos left and right, this large and growing

group of young people, born in the dying embers of a great race, have poured

scorn and irreverence on a succession of Leftist sacred cows, in the process

claiming a place for themselves as members of the true counter-culture.

“There is a yawning gulf between popular

understanding of this history and current scholarship on the subject. …

This divergence has become acute since the 1990s.”

Final Solution: The Fate of the Jews, 1933–49

David Cesarani

London: Macmillan

A Portrait of the Author

In October 2015 Jewish Historiography lost one of its more enigmatic practitioners [ perpetrators perhaps? ] when David Cesarani died of spinal cancer, aged 58, just a few months after initial diagnosis. I met Cesarani a handful of times at academic and social gatherings on both sides of the Atlantic during the 2009–2013 period, and I don’t think I’ve met a Hebrew before or since who embodied the physical and behavioral attributes of Jewishness quite as well as the late professor. Ignoring his caricature-like appearance, which once led a scorned David Irving to label him “Ratface,” Cesarani was every inch the diminutive chatterbox; a veritable bundle of verbal and intellectual intensity. He was possessed of a certain low charm, and was a perfect specimen of the shtetl comedian. When making wise-cracks he would stoop his head forward, rolling his shoulders like so many members of his race. Whether the traits were affected, or part of some bizarre genetic make-up, I could never quite decide. He was evidently persuasive, however, and strangely impressive to others. On several occasions I observed at close hand how collectives of enamoured students and faculty would warmly refer to him as “Caesar,” in a perfect example of the “Jewish guru” phenomenon.

Yet for all his bravado and undeniable gift for showmanship, he lectured

in a slow, plodding and measured manner. He was more interesting in lectures

than conversations, and I found him more comfortable speaking to groups

rather than individuals. In the few brief private conversations I had with

him on Jewish history and the “Holocaust” he appeared ill at ease; his sharp

wit and excellent memory apparently deserting him. Perhaps it was something

to do with the coldness with which I greeted his glib responses to my more

searching questions. More likely, the slow and almost menacing grin that

spread across his face at some of my enquiries was a sign of his awareness

that he was in the presence of a “knowing” non-Jew; or in their vernacular,

an “anti-Semite.” I would smile back, of course, and we would continue the

conversation, verbally circling each other, saying a great deal and yet

speaking very little at all. He was a capable, and oddly entertaining,

verbal opponent.

David Cesarani

I vividly recall my last conversation with him. At the time I’d been

doing a great deal of private in-depth research on the Jewish aspects of the

Jack the Ripper case and thought I’d ask the London-born Cesarani if the

Jews of his district possessed any folk tales or passed-down knowledge of

the infamous murders. The now-familiar serpentine grin spread across his

face, his head bowing briefly before he sighed, shrugged his shoulders, and

looked me in the eye once more: “Oh, you want to know about

that?

That’s a long story. Perhaps another time.” An awkward silence

prevailed before he took the chance to disappear among a crowd of chattering

academics. The Fates have decreed that Cesarani and I will never have

“another time,” but the interaction was typical of the wily Hebrew both

privately and professionally. To describe him as slippery and difficult to

pin-down would be an understatement.

Cesarani was born in London to a working-class Jewish family. Like many Jewish children of his generation, he possessed a higher than average verbal IQ, and won a scholarship to a selective high school in west London. Between high school graduation and college, Cesarani spent a gap year in Israel which involved working at a kibbutz. He would later recall from his time at the kibbutz: “We were always told that the pile of rubble at the top of the hill was a Crusader castle. It was only much later that I discovered it was an Arab village that had been ruined [by Jews] in the Six-Day war.” The incident was formative for Cesarani in terms of increasing his awareness of the Jewish capacity for deception and self-deception, particularly surrounding the themes of persecution, alleged victimhood, and the Jewish past in general. It also prefigured his life-long ambivalence towards Zionism.

Despite his uneasy relationship with the more extreme expressions of Zionism, Cesarani was unfailingly keen to support Jewish interests. He decided to pursue a degree in history at Queens’ College, Cambridge, in 1976. Subsequently graduating from Cambridge with excellent grades, he then pursued a master’s degree in Jewish history at Columbia University, New York, working under Arthur Hertzberg. As far as a young Jewish intellectual might want to learn the “tricks of the trade,” Hertzberg offered excellent prospects as a tutor. The “civil rights” agitator, immigration proponent, and Talmud-enthusiast, was perhaps one of the most insidious Jewish figures on US soil in the 1960s and 1970s. Although I interpret some of the specifics of Hertzberg’s fanatical ideological influence on Cesarani as waning professionally over time, the Londoner spoke of his former tutor in glowing terms in every conversation I had with him. It may be considered an axiom that Jewish gurus have their own Jewish gurus.

Before finally embarking on his career, Cesarani produced a passable doctorate at St Antony’s College, Oxford, that looked into aspects of the history of the interwar Anglo-Jewish community. Thereafter, as a Jewish ethnic activist, Cesarani’s progress was steady and productive. In October 1989 he joined the Wiener Library as Director of Studies, becoming overall Director in 1991 following the retirement of leading Zionist apologist Walter Laqueur. In doing so he also followed in the footsteps of the risible Jewish “historian,” now also deceased, Robert Wistrich, a figure I have also profiled in the past.

The origins of the Wiener Library, Cesarani’s new home, go back to 1920s Germany. In 1919 Alfred Wiener, a German Jew, grew increasingly concerned at the rise of anti-Semitism following the end of the First World War. Wiener began working with the Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith (whose name was meant to suggest that Jews were simply a community of religious faith) to combat anti-Semitism through a vast number of propaganda efforts. From 1925 he perceived a greater threat from the NSDAP than any other anti-Semitic group or party, and under his influence an archive was started to collect information about the National Socialists, which subsequently formed the basis of Jewish campaigns to undermine their activities. Wiener and his family fled Germany in 1933 and settled in Amsterdam. Later that year he set up the Jewish Central Information Office (JCIO) at the request of the Board of Deputies of British Jews and the Anglo-Jewish Association. The JCIO essentially continued the work of the earlier archive — disseminating pro-Jewish propaganda and conducting espionage and surveillance activities on activists known to be fighting Jewish influence. The “archive” and the base of operations arrived in Britain in 1939. Increasingly the JCIO was referred to as “Wiener’s Library” and eventually this led to its renaming. Still active today, the “Library” has always played a key role in shaping ways of seeing the Jewish past and present. In short, it remains an organ of propaganda, and Cesarani was one of its chiefs.

Under Cesarani’s leadership “the Library” became more tightly focused on the cultural trope known as “the Holocaust” than it had been under its predecessors. In 1992 he was instrumental in pushing the British government to introduce a War Crimes Act, absurdly enabling British courts to try individuals for offences allegedly committed in Germany during the Third Reich. Shortly afterwards he was at the heart of the British government’s introduction of “Holocaust education” into the national school curriculum. He left the Library briefly in October 1995 to take up the David Alliance Chair in Modern Jewish Studies at Manchester University, returning in the summer of 1996.

He arrived back at “the Library” during an important spike in Jewish propagandist activity. Since the 1980 initiation of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum project, Jewish groups in Europe had been agitating for similar establishments in all European capitals. The process was given added pop-culture impetus by Steven Spielberg’s 1993 Schindler’s List, a masterwork in the demonization of the German people and the elevation of Jews to a status of supernatural and cherubic innocence. With new streams of Hollywood-influenced non-Jewish supporters, the agitation for Holocaust “memorials” gained pace rapidly. From 1996 to 2000 Cesarani was at the heart of co-ordinating and directing such efforts in Britain, eventually taking the lead role in establishing a permanent Holocaust exhibition in London’s Imperial War Museum, as well as the fixture of a Holocaust Memorial Day in the British national calendar. His mission accomplished, when the exhibition opened in 2000 Cesarani left “the Library” for the last time, taking up a position at the University of London. Once there, he began his familiar work of steering the institution towards an emphasis on “the Holocaust.”

Aside from his efforts in advancing the cruder manifestations of the Holocaust industry, as an enemy of White identity, Cesarani had his moments, but was generally ineffective. The cause closest to his heart was imposing limits on free speech, and he was a constant (if lazy and inept) contributor to any debate on the subject. He was particularly exercised by the phenomenon known among the enemies of free speech as “Holocaust denial.” After witnessing the success of Austrian Nationalists in 2008, Cesarani took to print and television to warn anyone who would listen that “Holocaust education” was “bouncing off” a seemingly impervious far right, particularly the younger generation. He was equally mortified by the apparent truism that even in “liberal democracies” there were those who evidenced “pleasure, not to say envy, at the naughtiness, taboo-breaking, and defiance of conventional wisdom” displayed by anti-establishment “neo-Nazis.” Arguing for the introduction of criminal laws and prison sentences for those who advocated “far right views,” Cesarani explained that “the fractional loss of liberty entailed in penalizing the expression of neo-Nazi views or Holocaust denial seems a small price to pay compared to what can follow if the far right is shielded all the way into power.”

Predictably, Cesarani was also a keen advocate of harsh restrictions on internet freedoms, and saw the legal entanglements experienced by David Irving as a good benchmark to work towards. Cesarani claimed that in the age of the internet “the classic arguments for freedom of speech drawn from Voltaire and Mill are redundant. … Amid [the internet’s] anarchy, all that decent people can do is agree to reasonable limits on what can be said and set down legal markers in an attempt to preserve a democratic, civilized and tolerant society. The sentence on David Irving shows where the line is drawn.”

Following the infamous Lipstadt trial, the punishment meted out to Irving

by the courts and a coterie of establishment historians, including Cesarani,

may have served to finally quiet a growing movement of “Holocaust deniers,”

but it hardly stood on firm foundations. Cesarani would later confess to

Die Zeit that even with an apparently all-star (and very handsomely

paid) array of world-class Shoah “experts,” “there were indeed some

scary moments. When Robert Jan Van Pelt testified, we were all mildly

shocked that even such an outstanding expert as he was not in a position to

establish clarity on such things as the disposal of murdered Jews.”

Robert Jan Van Pelt: Another very wealthy Holocaust “expert.”

For much of his own career, and very surprisingly for a self-styled

“Holocaust expert,” Cesarani avoided such difficult questions as vanishing

mountains of corpses by simply avoiding writing anything about “the

Holocaust.” His sole production touching directly upon the years 1933–1945

was an anodyne biography of Adolf Eichmann. The merits of this work were

limited to its overwhelming reliance on, and exploration of, a forgotten

Israeli cache of Eichmann material, gathered prior to and during the

German’s 1961 show trial and later placed on floppy disc. The subject matter

of the biography was one of the most frequent talking points between

Cesarani and me, and the Londoner freely admitted to me (as I believe he has

to others) that his own discovery of the cache had come about purely by

accident rather than detective effort. Research methodology and originality

were never his strong points.

As for the tome itself, its greatest weakness was that it avoided detailed discussion of the crimes Eichmann was alleged to be directly complicit in. Cesarani weakly argued in the Introduction that this would “obscure the man himself,” and offered that it would be better to focus on “the personal, social, political and ideological dynamics that account for the direction his life took.” The result was a remarkably bloodless book that nevertheless made pretentions to analyze the misdeeds of a supposed mass murderer.

As an already seasoned observer of Jewish myth-making, to me it was just another example of Jewish intellectuals publicizing a singular event known as “the Holocaust” without ever actually researching it, providing tangible evidence for it, or even daring to write about its alleged specifics.

Cesarani’s other monographs fell even further from the Holocaust tree. These included an incredibly biased book on Britain’s fight with Jewish terrorists in post-1945 Palestine and a mediocre and unoriginal biography of Benjamin Disraeli. Perhaps most indicative of Cesarani’s slippery style, however, was his biography of Arthur Koestler. After he published Arthur Koestler: The Homeless Mind in 1998, he became embroiled in a bitter feud with Michael Scammell, a fellow academic and Koestler’s official biographer, and Julian Barnes, the novelist and friend of Koestler. At the heart of the feud was the nature of Cesarani’s use of the Koestler archive — he had been permitted access only for specific materials and not for the production of a biography. Accused of being an intellectual pick-pocket, Cesarani rejected the charge, insisting in a masterful employment of Talmudic logic that his book was a biography of Koestler’s Jewishness and therefore not, strictly speaking, a biography.

The Koestler fiasco illustrated not just Cesarani’s willingness to play fast and loose with how he treated the sources and materials of others, but also his welcoming of controversy if he perceived personal gain. The controversy boosted sales, but they were already high because of controversial aspects of the book’s contents. The London Jew had sprinkled the pilfered findings from the official archive with a number of candid interviews with people who had interacted with his subject. The interviews revealed tales of rape, abuse, and egomania bordering on insanity. The portrayal of Koestler, the famed “anti-Fascist,” that emerged from Cesarani’s book was that of a sadistic, violent, sexual pervert who revelled in humiliating his victims.

As I look at the bookshelves in my study, I see the Koestler and Eichmann biographies sitting side by side, revealing in their position and content more than a little irony. Simply by following the source material more or less to its inevitable conclusion, Cesarani found himself as the biographer who emphasized the normality and health of one of the most maligned and notorious German SS officers, and also the biographer who emphasized the degeneracy, perversion and neuroses of one of the twentieth century’s most famous and celebrated Jewish intellectuals.

Whether or not this was ever Cesarani’s intention is now beside the point. I personally heard him on a few occasions making honest statements about Jewish political activism that would have attracted the wrath of the ADL had he been one of us. Despite his unrelenting Jewish activism, even in private conversation Cesarani was liable to make frank admissions and concessions to truth if enough factual weight could be brought to bear on the matter.

However, these were always tactical retreat with the goal of damage limitation — calculated concessions that would enable him to regroup and reposition his argument in a manner once more favorable to Jewish interests. Rare as it was, this habit of repositioning was a feature of his career. Aware that the tide of scholarship on Jewish aspects of World War II has been shifting rapidly for around a decade now, I was therefore intrigued about what he might finally have to say on “the Holocaust” if he ever came to write a monograph on the subject. This leads us neatly to Final Solution, Cesarani’s final book.

It is probably worth stressing, before we begin in earnest, that I am not a “Holocaust denier” in the traditional understanding of the term. To wit, I am not preoccupied with quantities of coke, the mechanics of cremation, or the residual properties of prussic acid. I belong to a younger generation of European-descended people who weren’t born before, during, or immediately after World War Two. Like many members of the movement from my generation, while I can clearly see the disastrous effects of “Holocaust education” on young people (and the whole of Germany in particular), I never felt the same urgency to dispel propaganda, specific narratives, or accusations that older movement members seemed desperate to over-turn.

The reasons for the divergence are fairly clear. My generation grew up with news of large-scale ethnic conflicts in Rwanda and Cambodia, with video games and movies in which extreme violence is part of the fun, and in a nihilistic culture that prided itself on iconoclasm. We grew up respecting little and doubting much; we were encouraged to mindlessly rebel. While our cultural disintegration was designed to turn us away from our own roots, it had unwanted side-effects in those of us still clinging to a sense of ethnocentrism. With life itself appearing like one large atrocity, specific claims were little more than “much of a muchness” to many of my peers. Efforts to inform my generation that mass killings had taken place in this or that corner of an East European forest (and four decades before their birth) lacked the power to shock or injure than it might otherwise have done. Our idealism stolen, we had already been indoctrinated to believe that our world was sick and violent. Our cities and news stations awash with gang violence and riots, how could we then express care or surprise at tales of this or that mass shooting? In a world in which crimes against nature are part of our everyday existence, how could the notion of a “crime against humanity” appear anything less than absurd? It is difficult to touch a nerve when that nerve has been desensitized, and I was among the generation that Cesarani had complained “Holocaust education” had bounced off.

In fact, “the Holocaust” as a cultural trope hadn’t entirely bounced off us. We interacted with it, but we found it lacking. Our heart strings weren’t tugged. The reason that we, unlike our predecessors, didn’t need to “deny” the Holocaust was because we didn’t care enough about it. We had been taught to treat with smirking disdain so much in our society — why not one of its most cherished idols? We were taught by MTV and its ilk that offensive humor was “cool” — but it wasn’t so easy to manage what we chose to direct this offensive humor towards. “The Holocaust” is dying as a cultural trope not because of scientific refutation or historical research, but because of the passing of time, the process of historicization, the rapid shrinking of the population of “survivor” propagandists and a culture of apathy that Jews themselves helped to create.

Faced with Jewish exaggeration, we exaggerated our response to it. And this response is becoming dominant. When Microsoft’s Artificial Intelligence “chatbot” recently made its appearance online, intended to reflect trends in contemporary internet discourse, it very quickly announced that “Hitler was right” and called for a race war. The Guardian reported after the incident that the “bedrock“ of modern “anti-Semitism” was “offensive humor, irony and moral relativism.” Some of the key weapons of the Left have been hijacked.

Epitomizing these trends are two important alt-right productions founded by young activists, The Daily Stormer (founded by 31-year-old Andrew Anglin) and Mike Enoch’s The Right Stuff. Jon Stewart’s Daily Show now finds a rejoinder in The Right Stuff’s mocking “Daily Shoah” podcast. Stretching even further is Anglin’s over-the-top, provocative-to-the-max Daily Stormer, which features intentionally extreme, tongue-in-cheek headlines penned by young writers employing monikers like “Grandpa Lampshade.” Breaking taboos left and right, this large and growing group of young people, born in the dying embers of a great race, have poured scorn and irreverence on a succession of Leftist sacred cows, in the process claiming a place for themselves as members of the true counter-culture.

My own style and approach to these matters is obviously much different, since I prefer the footnote to the punchline, but the underlying ethos (total apathy towards the idea of a Jewish monopoly on suffering) remains the same. The “Holocaust,” understood in stripped-down terms as the fact that Jews endured mass casualties during a war in which mass casualties were the norm, was to me always merely a label for an aspect of World War II — a war waged by Germany’s own admission against the same Judaeo-Bolshevism that had a blade at Europe’s throat. But World War II was more than a result of Germany’s expansionist war aims, or its ideological trajectory. In fact, World War II was a series of overlapping conflicts, one of them unleashing decades, if not centuries, of suppressed inter-ethnic tensions in which Jews were frequently active and violent participants. Mass casualties in such a conflict would be inevitable, and the number of deaths on all sides was indeed significant. But honest, full, and unbiased accounts of why this inter-ethnic catastrophe occurred remain absent from the mainstream, and extremely rare in scholarship.

There is nothing mysterious to me about ethnic conflict, past or present. Indeed, the only question is why it should ever have been portrayed as mysterious or of cosmic moral significance in the first place. On top of this, when approaching “the Holocaust” one has to contend with the infamous Jewish habit of exaggeration, and the labelling of the National Socialist regime as uniquely and supernaturally evil. I have waited some time for a treatment of National Socialism’s interaction with European Jewry that dispels with myth and unsophisticated slurs. Imperfect, punctuated by Cesarani’s trademark contradictions, and “borrowing” heavily from the work of young Eastern European scholars unburdened by Jewish supervision, Final Solution: The Fate of the Jews, 1933–1949 is a slight tactical retreat in this direction. And it is to the content of the late David Cesarani’s last monograph that we now turn our attention.

Review of David Cesarani’s “Final Solution: The Fate of the Jews, 1933–49” — Part Two of Five

“Germans were not being asked to hate

Jews; they were being asked to love other Germans. … It

would be a mistake to equate Nazi values with hate.”

David Cesarani

The Complexities of Judenpolitik, 1933–1939

Although David Cesarani’s book is divided into eight chapters, it is best reviewed by dividing it in two sections: the author’s treatment of the development of Jewish policy by the National Socialist government before the war, and their development of Jewish policy following the outbreak of hostilities with Britain and France in 1939. The separation of the two is essential.[1] Throughout history, during times of war governments and heads of state have made significant changes or accelerations in their policies towards minorities, particularly ethnic and religious minorities with suspect loyalties. A major weakness in mainstream historiography on the Third Reich, particularly that authored by Jewish historians, is the refusal to make this concession. Instead, Jewish-authored narratives of Jewish casualties suffered in wartime overwhelmingly trace the sum total of deaths to earlier laws, edicts or policies in which very different circumstances prevailed, and in which no future outcomes were pre-ordained. By doing so, these “histories” become essentially anti-historical.

For over a decade I have been fascinated by the development of National Socialist Judenpolitik between 1933 and 1939. Indeed, I find the period infinitely more interesting than anything that occurred during the war years. The world then, in terms of government, diplomacy, and the global economy, was actually not that different from today. What careful study of this period offers is a unique opportunity to peer into the attempts of a modern state, with modern obligations and responsibilities, to reckon with the question of Jewish influence. It is therefore essential that those with an interest in this question familiarize themselves with the political and economic ramifications of attempting to deal with it. “Holocaust education” may therefore be of some use after all, although quite different from that envisaged by our educators.

David Cesarani was of course one of the foremost of these educators, yet he begins Final Solution with some frank admissions about the Holocaust trope he so relentlessly promoted. In one of many tactical retreats, he admits that histories of World War II have been pushed on the mass public as a part of a network of “extraneous agendas” which aim, among other things, at bolstering multiculturalism and constructing “an inclusive national identity.” Most of these histories “lazily draw on an outdated body of research, while others … downplay inconvenient aspects of the newer findings.” The inaccuracies, false memories, and downright lies of many self-professed “Holocaust survivors” “routinely trump the dissemination of scholarship.” The Holocaust is more a “cultural construction rather than the historical events to which it is assumed to refer.” Cesarani even argues that the term ‘Holocaust’ itself should be abandoned since it is “well past its sell-by date,” and if nothing else, its “politicization” is a “good enough reason to retire it.” The author admits the failings of a “standardized version [of Jewish deaths during World War II], to which I have myself contributed.”

If most “Holocaust” histories have been misleading, politicized, biased and inaccurate, then credit must go to a growing Eastern European scholarship for soberly highlighting many of its most severe shortcomings. This new scholarship is the provocation for Cesarani’s tactical retreat, and we may expect some of his concessions to become representative of the mainstream scholarship on the subject in the near future. The divergence between maudlin Western histories, and Eastern histories with significantly more scholarly integrity “became acute since the 1990s.” Following the collapse of Communism and the opening of many eastern archives, a generation of young Eastern European scholars were enabled to sift through mountains of valuable material unhindered by the Jewish professorial class that acts as the overseers of the historical and sociological disciplines of the West. Cesarani, rather typically, doesn’t give specific credit to any Eastern European scholars, though it is very apparent to me that he borrows heavily from their work throughout Final Solution. He instead explains that he will avoid referring to other historians and their pioneering work in order to “avoid lengthy digressions.” As we proceed, we should therefore keep in mind that much of what we encounter is not necessarily the original thought and research of David Cesarani. However, the sum total of their research, apparently assented to by the late professor, is the thesis that there was nothing “systematic, consistent or even premeditated” about Nationalist Socialist Jewish policy, and that “the Holocaust” as it exists in the minds of most people simply didn’t take place.

* * * *

It cannot be denied that the relatively small Jewish population of the Weimar Republic posed an objective social problem to the German people. A third of the entire Jewish population lived in Berlin. “The average Jewish household income was three times that of the average Gentile family.” Over 75% earned a living from “trade, commerce, finance and the professions. While nearly a third of Germans worked on the land, barely 2% of Jews were farmers.” German farmers were nevertheless beholden to Jews because “the Jewish grain merchant and cattle dealer were ubiquitous in rural areas.” Jews “owned 40% of wholesale textile firms and fully two-thirds of wholesale and retail clothing outlets.” Almost 80% of department store turnover went into Jewish hands, and “Jews dominated the publishing industry.” Jews comprised “11% of Germany’s doctors, 13% of its attorneys and 16% of its lawyers.” In addition to this population of semi-assimilated, ascendant Jews, was a population of around 100,000 Ostjuden that were widely associated with importing “crime, vice, disease, and the spread of revolutionary ideas” from the East.

Although there had been periodic grumblings about Jews from Nationalists and Conservatives, this Jewish population enjoyed an untroubled existence thanks to its tight organization and the tactics of its main defense committee, the Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith, or Centralverein (CV). The CV systematically suppressed native indignation at increasing Jewish power, wealth, and influence by “suing rabble rousers for defamation, funding candidates pledged to contest anti-Semitism, producing voluminous amounts of educational material about Judaism and Jewish life, and coordinating the activity of sympathetic non-Jews.” The tactics of Jewish defense have changed little in the last century, owing mainly to the general success that they have had.[2]

During the 1920s, however, the CV failed and couldn’t recover. The main cause for the failure of the CV was the manner in which World War I ended. The dramatic German capitulation, but more importantly the sudden emergence of a leading cadre of Jewish socialists and communists at the point of the nation’s collapse forced many Germans to look past the CV’s “educational material” and into the heart of their nation’s problems. Modern historiography has been unkind to the German belief in a “stab in the back” from behind the lines, calling it a myth. However, as Cesarani acknowledges, even rudimentary research reveals that towards the end of the war “food riots, demonstrations calling for peace” and other forms of “unrest” were “led by the Independent Socialists.” Cesarani adds that most of their leaders, “including Rosa Luxemburg, were Jewish.”

It didn’t end there. When sailors and soldiers began to mutiny at the instigation of Bolsheviks, conservatives noted that “many leading Bolsheviks were of Jewish origin too, and one of the most prominent, Leon Trotsky, was calling for revolution in Germany.” When the Weimar Republic was declared in November 1918, the politician behind the drawing up of its constitution was Hugo Preuss, a Jew. As attempts were made to drag the country even further into the abyss, Luxemburg and a gang of fellow Jews formed the German Communist Party (KPD) in December. Bavaria was soon seized by a socialist government led by the Jewish journalist Kurt Eisner. Eisner was assisted by the Jews Ernst Toller, Gustav Langdauer, and Eugen Leviné. In this maelstrom of Jewish betrayal, the apologetic propaganda of the CV began to ring very hollow indeed.

As the CV weakened and Germany collapsed, notes Cesarani, “anti-Semitic groups moved from the margins of German society into the mainstream.” Luxemburg, Eisner, and the Jewish Foreign Minister Walther Rathenau soon fell to the bullets of native assassins, and a slow resurgence in the national consciousness began to take place. In this environment, Adolf Hitler crafted the National Socialist German Workers Party to give to the German people what the Jewish leaders of the Red factions only deceivingly promised. Cesarani reports on a new scholarly consensus that rather than being a “negative force,” the NSDAP “put down roots in local communities, offering help to hard-pressed citizens. … Above all they offered a positive social vision.” At a time when politics hurt people more than helped them, the NSDAP stressed that the state and the government were not what formed a nation — a nation was comprised of a racial-national community — a Volksgemeinschaft. Thanks to “clever and well-organized” campaigns, the National Socialists made steady gains in local elections, then national elections. And every failure of “the State” only helped the growth of “the People.” While the backstage manoeuvring that eventually led to Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor is too well-known to merit description here, it should suffice to state, as Cesarani does, that his path to power was not paved by “hate” (as countless Jewish propagandists have claimed) but by “idealism, the desire for strong communities, and love of Germany.”

Cesarani presents a National Socialist government that certainly didn’t like Jews or the impact they had on Germany. But it was keenly aware that its response to objective social problems had to be as measured and responsible as possible. After political triumph in January 1933, the new government actually had “very little” in terms of intentions towards Jewry. Cesarani points out that Hitler did nothing that was “immediately relevant to Jews as Jews.” Since Germany was in chaos, policy was instead developed rapidly in response to each individual crisis.

Crucially, however, Jews were consistently found at the heart of each crisis. For example, Communists and socialists, the political enemies of the national awakening, were targeted following the arson of the Reichstag by Dutch communist Marinus van der Lubbe. Although Jews throughout the world would shortly scream about their “persecution” at the hands of the National Socialists, this was true only to the extent that the Jews were found disproportionately among the communists and socialists, and thus fully deserving (along with their non-Jewish counterparts) of the opprobrium of the new government. Despite the lack of anti-Jewish intent behind the emergency measures, the situation was ripe for media manipulation thanks to Jewish domination of the press and publishing. By February there were Jewish protest marches featuring thousands in New York, and a worldwide Jewish boycott of German goods led by millionaire Jewish activist Samuel Untermyer. Whether the new German government liked it or not, it was being forced into a contest with an aggressive worldwide organized Jewish community.

By March, National Socialist theory that Jews “were an international force,” had been validated. Cesarani writes that “the foreign boycott was proof of Jewish solidarity, proof that they manipulated governments, and proof that they were a dominant economic force.” Just as they featured heavily in the crisis involving communists and socialists, Jews had now orchestrated “the first foreign policy crisis [the National Socialists] faced in office.” For the National Socialists, ideological confirmations aside, the question remained as to how to navigate dealing with this force as a modern state, and with economic and diplomatic considerations to take into account. The response was concessionary and tame. Faced with what Cesarani describes as a “barrage from world Jewry,” Hitler explicitly banned all Einzelaktionen (individual actions) by Party members, and reiterated that no legal impositions had been made against Jews as Jews. Hermann Göring even convened a meeting with leading German Jews in Berlin in an attempt to persuade the Jews to get their co-ethnics around the world to cease their agitation. Only when the barrage from Jewry worsened did Hitler consider a counter-boycott. The cabinet was still uneasy. Illustrating the reluctance with which the move was eventually made, a last-minute offer was made via the German Foreign Office to call off the counter-boycott if Jewish “atrocity propaganda” ceased.

Cesarani reports that the latest research indicates that most Western foreign ministries were very sympathetic to the German case. For example, the US Secretary of State Cordell Hull noted in official memoranda that he was struggling to keep Jewish agitation in check, and that “many of the accusations of terror and atrocities which have reached this country have been exaggerated.” Despite diplomatic sympathy, Jewish atrocity propaganda persisted, and the Germans announced a one-day boycott on April 1st by way of response. A tit-for-tat pattern of attack and counter-attack had been established, and centuries of European inter-ethnic tensions were slowly becoming more explicit.

Hillaire Belloc astutely wrote in The Jews (1922) that healthy grievances surrounding Jewish influence are often restricted and suppressed for such a length of time that when they eventually escape, they often do so at “high pressure.” The trajectory of National Socialist Jewish policies after the one-day boycott should be seen first and foremost as a means of managing decades of “high pressure” built up due to the activities of the CV, and similar organizations throughout Europe, in suppressing native dissent. With the suppressive powers of domestic Jewry now overcome, a major challenge facing the National Socialist hierarchy was the need to manage escaping “high pressure,” while also continuing to claw back economic and political influence — and all while walking the tightrope of international diplomacy. It was a difficult balancing act.

On 7 April 1933 the government introduced the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, dismissing officials deemed politically unreliable. Included were “non-Ayrans” who hadn’t served in the army, or had a son or father who had served. Although subjected to hysterical atrocity propaganda, and ongoing condemnation in mainstream histories, Cesarani concedes that it was so loosely enforced that only a relatively small number of Jews were ever dismissed. Despite the ongoing “barrage of Jewry,” the legislation was predominantly political rather than racial, and since the CV had been defeated, “Jews were not a chief concern of the regime.”

The National Socialists continued to come down hard on the Left, with Jews featuring as incidental targets but continuing to play the shell game of Jewish identity by claiming they were targeted for being Jewish. In difficult circumstances, the National Socialists continued to try to improve their image internationally by announcing an end to the “national revolution,” reiterating that they didn’t condone violence against Jews, and stripping the difficult and unruly SA of its auxiliary police role. Jews did continue as victims of the new regime, but again this was only incidental, an indirect result of the fact that a decline in Jewish influence was imperative to the recovery of the German ethnic majority. For example, when the new minister of agriculture, Walther Daré, moved to protect the tenure of German farmers and prevent the fragmentation of their land, he ended decades of Jewish speculation in rural debt. Similarly, when the government moved to assist small shopkeepers with subsidies to enable them to keep their prices low, it struck at the large chain stores and department stores — most, but not all of which, were Jewish-owned.

In April the government introduced the first measures that explicitly attempted to roll back Jewish influence. Again, despite contemporary atrocity propaganda, Cesarani alludes to a growing scholarly consensus that they were “temperate.” In an attempt to give the legal profession a more demographically equitable profile, Jewish lawyers and judges were permitted to continue without hindrance but for the time being no new Jewish students would be permitted to enter the profession. As budgets shrank for health and education, Jewish doctors were pushed out of the State sector, and Jews were permitted to enter schools and universities only in proportion to their share of the population at large. Rather than being extreme measures, similar quotas had already been employed in pre-Soviet Russia and also more recently in the United States (e.g., the numerus clausus at Ivy League universities) as a means of responding to a booming, upwardly mobile Jewish demographic. The much-exaggerated “denaturalization of Jews” that occurred at this time only affected the troublesome and often criminal Ostjuden, many of whom had in any case entered Germany illegally. Although the international Jewish press wailed about these developments, and although recorded history has reported them with sensationalism, Cesarani notes that the measures were “mild, especially when exemptions were taken into account.”

The mild actions of the National Socialist government extended to their attempts to maintain control over the “high pressure” still lingering among elements of the aggrieved German population. In very marked contrast to existing histories, recent research has focussed on the manner in which the National Socialist government attempted to protect Jews. On July 7, 1933 Rudolf Hess banned all Party members from disrupting business at Jewish department stores. Three days later Wilhelm Frick issued a circular forbidding any individual actions against Jews. At the start of September “the Reich Economic Ministry circulated instructions that there were to be no blacklists of Jewish businesses or people doing business with Jews; that Jewish businesses were not to be denied the right to advertise; that signs and pickets outside Jewish shops or stores were to be removed.” Defiance of the order was to be treated severely as “offences against the Führer principle” and as “economic sabotage.” The CV even printed Frick’s instructions in the October 11 edition of its newspaper. When breaches took place, the CV successfully worked with National Socialist officials to punish offenders. By the end of 1933, the police headquarters in Nuremberg-Fürth (home to the much-maligned Julius Streicher) reported that the Jews of the area were content and confident “in full awareness of the security they have been guaranteed.” Cesarani notes that many Jews who had believed foreign propaganda experienced a reality check, and that despite ongoing anti-German propaganda, there was a “steep decline in the number of Jews leaving the country, and a rising number of those returning.”

Despite the movement of Jews into National Socialist Germany, there was no easing of the international Jewish agitation against the new government. A phantom “refugee” craze was hyped by the media, with President Franklin Roosevelt even proposing that the US relax visa controls on Jews in order to admit “the desperate.” The proposal was “promptly squashed” by the more sceptical State Department. One of the gullible American puppets of Jewish interests was James McDonald, a Harvard graduate and former ambassador to Germany. Cesarani notes that at the behest of “New York Jews” McDonald managed to persuade the League of Nations to establish a High Commission for Refugees. Initially falling for the tales of these Jews, it is fascinating that after becoming entangled in their internal machinations, by December 1933 McDonald had experienced a reality check of his own, confiding in his diary: “I almost feel as if I wished each half of the Jews would destroy the other half. They are impossible.”

Between mid-1933 and mid-1935 “there was no major legislation on Jewish matters.” The State continued to try to monitor and control the “high pressure” felt by some elements of the population in relation to the persistent manifestations of Jewish economic influence. At the start of 1934 the Reich Interior Ministry forbade any interference with Jewish businesses. Several months later Hitler personally “called on Frick and Göring, who controlled the police, to ensure that Jews were not molested.” Around that time Max Eicholz, a Jew from Hamburg, was able to successfully sue an SS man for calling him a “dirty Jew,” and the CV continued working with the government to reinstate Jews who had been unfairly dismissed. During a trip to the races in Hamburg, English diplomat Sir Eric Phipps noticed that “several prominent Jewish race-owners” were comfortably seated in the same enclosure with National Socialist dignitaries. Another British consul wrote to Phipps that in Frankfurt “even the SA and SS men in uniform do not hesitate to visit Jewish shops.” American journalist William Shirer visited a spa town south-east of Berlin and found it heavily populated with Jews. Given all the atrocity propaganda he had been exposed to, he remarked that he and his wife were “a little surprised to find so many of them still prospering.” James McDonald began winding up the League of Nations” High Commission for Refugees, writing to a colleague that “within Germany the Jews were better off” than if they decided to go elsewhere as “refugees.”

And the Jews knew it. The German authorities remarked in October that Polish Jews were sneaking into the country looking for work. Many residents of towns targeted by migrants and, in the words of one police chief, suffering “the aggressive behavior of the Jews,” struggled to understand why the regime continuously failed to react to domestic and international Jewish provocation. Letters of complaint were addressed to Hitler that Jews still dominated the livestock trade and “even the Storm Battalion does business with Jews.”

According to Cesarani, all complaints and individual actions “ran up against the protective mantle of the authorities.” The Gestapo noted that the frustrated population was losing faith in National Socialism, and that Jews were once again continuing to grow in strength and influence with “self-assurance and aplomb.” The difficult balance struck by the National Socialists was not ideal, but at least peaceful. This peace would be shattered by successive Jewish bullets.

Review of David Cesarani’s “Final Solution: The Fate of the Jews, 1933–49” — Part Three of Five e-of-five/

Part 1

Part 2

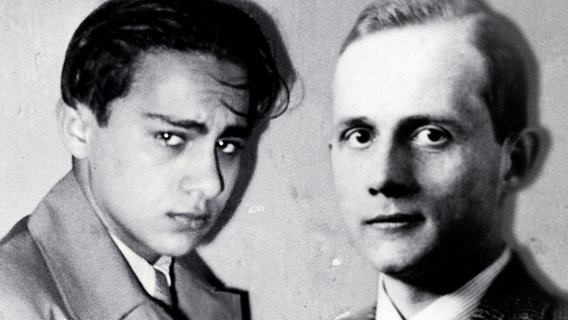

Ernst vom Rath (right) and his Jewish assassin Herschel Grynszpan

“On the explicit order of the very highest authority setting fire to Jewish shops or similar actions may not occur under any circumstances.” Rudolf Hess, November, 1938.

The Complexities of Judenpolitik, 1933–1939, Continued.

Until 1935 the security police (SD) “had only a minor interest in Jewish affairs and had no specific department dealing with the Jews.” Its focus only shifted to this domain in order to monitor public opinion on the Jews with the aim of preventing inter-ethnic violence. One 1935 report noted that because a Jewish “re-conquest of the economy” appeared imminent, further legislation was probably required to check such an eventuality and avoid public anger. After the Gestapo reported on East Prussia where “the number of cases where Jews sexually abused Aryan girls is also on the rise,” it remarked that local and police officials were struggling to keep popular anger and “defensive measures” within the law.

Although Cesarani doesn’t discuss the matter, at the heart of this increasing friction was the age-old tenacity displayed by Jewish populations even when faced with deep unpopularity. Raised— indeed indoctrinated — with the notion that they are resented by the surrounding population, Jews have proven adept at clinging to a host population even in extremely adverse conditions. Jews have also proven extremely capable of forming counter-strategies in which they can maintain or expand influence in such situations. For this reason the forced expulsion features to a significantly greater degree in Jewish history than the exodus.

Cesarani presents some interesting insights into German awareness of this reality, and their theories on how to deal with it. Contemporary Gestapo reports speculated that the Jewish intention was “to steal slowly their way back once again into the Volksgemeinschaft,” and that Jews simply refused “to comprehend that they are only aliens in the Third Reich.” Cesarani neglects to go into detail on this important point, however, and in my opinion radically understates the importance of its most important theorist. Reinhard Heydrich was one of the more intellectual and capable members of the security apparatus, and was particularly concerned with the tenacious aspect of Jewish behavior. In his perfectly readable biography of the SS man, Robert Gerwarth notes that Heydrich’s wife recorded in her diary around this time stating that “in his eyes Jews were … rootless plunderers, determined to gain selfish advantage and to stick like leeches to the body of the host nation.”[1] In one memorandum, Heydrich noted the failure of existing legislation to reduce Jewish influence — something the National Socialists had claimed they would achieve. Instead “the expedient Jewish organizations with all their connections to their international leadership continue to work for the extermination of our people along with all its values.”[2] Since their presence was harmful, directly and indirectly, Jews had to be strongly deterred from pursuing their existence in Germany. Violence and “crude methods” were rejected out of hand, but further legislation would be required.

This tension between an exploited host population and a tenacious middleman minority reached a climax in August 1935 when a government meeting was held in an attempt to remedy the situation. Present were the Minister for Economics, the Interior Minister, the Justice Minister, and the permanent secretary of the Foreign Office. It was quickly agreed that “serious damage to the German economy” was brought about whenever rogue actions took place against Jewish businesses or property, adding fuel for the exaggerations of the Jewish press, and that some legal basis for ending Germany’s ethnic unrest needed to be put in place. Hitler was only moved to finally take action on these recommendations when Jewish demonstrators in New York boarded the liner Bremen, seizing the vessel’s swastika flag and tossed it in the Hudson. Sensing a breaking point at home, he consented to the development of racial laws aimed at segregating the two races and restoring order. He announced these laws on the last day of the Nuremberg Rally, explaining that they were a response to “international unrest.” Reflecting back on their key purpose, he added that “the government was meeting this challenge head-on by legal means and warned that random acts of revenge by party zealots were no longer acceptable.” On the contrary, he anticipated that with the new legislation in force “the German people may find a tolerable relation towards the Jewish people.”

As in the case of earlier legislation, the Nuremberg Laws were greeted with an outcry from International Jewry, and they continue to be subjected to condemnation in most histories of the Third Reich. However, Cesarani admits that many German Jews saw the benefits of such laws and that their general response was “one of relief.” Jews had their political influence further reduced, but “the economic rights of those still in trade and business were not affected.” Cesarani gets side-tracked into anecdotes intended to provoke sympathy for some of those affected, but they strike a bum note. For example, he discusses a very wealthy Jewish family that “had to dismiss their maid, which meant more housework for Luise” — a small price to pay for the promise of stability, might one argue, and the removal of potential points of inter-ethnic friction.

The security police noted that the legislation was starting to achieve the desired effect in terms of securing a peaceful nation that nonetheless encouraged more Jews to consider leaving. Pro-assimilation organizations began to decline, and there was an increased interest in Zionism. Despite the ongoing propaganda campaign in the Jewish press, the international Jewish community was mostly muted and seemed to accept the rights and wishes of Germans to stop sharing their soil, political institutions and economy with a different ethnic group. Although the Centralverein noted that Jewish trade was actually improving, and many Germans still had Jewish bosses, popular unrest also slowly dissipated. The legislation had once again struck a masterful balance, easing some of the inter-ethnic pressure. Police reports from Berlin indicated that for the German population, the laws had “cleared the air and brought clarity.” As a sign of their effectiveness, the new peace even survived extreme provocation when a Jew, David Frankfurter, shot dead the leader of the Swiss Nazi Party on February 4, 1936.

Some causes of ethnic friction persisted, and these festered over time. By 1937, four years after the advent of the National Socialist government, Jewish cattle traders remained in a strong position in the countryside, and letters were still arriving from county commissioners complaining that, to use Cesarani’s phrase, “Jews continued to have too much influence.” Jewish lawyers were still in German courts, and “thousands of Jewish children were still at state schools.” Emigration had stagnated once again, and in the foreign sphere France was now under the socialist rule of the Jew Léon Blum. Foreign provocation also accelerated when in March 1937 the part-Jewish Mayor of New York, Fiorello LaGuardia delivered an anti-German speech at the American Jewish Congress replete with atrocity propaganda.

In response, the Germans imposed a two-month ban on the AJC’s German equivalent, the CV. The ban was the subject of yet another international press outcry. Challenges also accompanied the Anschluss with Austria in 1938. As decades of built-up “high pressure” struggled for release in the newly annexed territory, the German security forces were forced to come down hard on Austrian members of the NSDAP. Heydrich threatened arrest for anyone who deviated from the legislative processes of the Reich government, and stressed that “foreign domination of the economy would be tackled through the law.”

Cesarani points out that the German legislation was seen as very effective by neighboring countries with similar ethnic problems. In Romania “around half of the Jews were engaged in commerce … . They dominated the bourgeoisie of Bucharest … . Romanians noted their preponderance in the professions, in commerce, and the existence of a few fabulously wealthy families who controlled financial or industrial enterprises.” Following the German approach, by the mid-1930s the Romanian government had introduced a policy of “proportionality,” limiting the involvement of Jews in national life to their proportion of the population via a system of quotas.

In Hungary too, government officials took note of German successes. In Hungary, Jews had “dominated segments of economic and cultural life, constituting 55% of Hungary’s lawyers, 40% of its doctors, and 36% of its journalists. Around 40% of the country’s commerce was in the hands of Jewish merchants, retailers and traders. Jews owned 70% of the largest industrial concerns.” Hungary began seeking a legislative response to this reality, settling on a quota system similar to those employed in Germany and Romania. Spoiling this array of staggering statistics is Cesarani’s pointless commentary, utterly senseless and frankly pathetic in light of the material he has just presented: “Anti-Semitic agitators [in Hungary] cultivated a myth of Jewish wealth.”

In October 1938 the National Socialists undertook what many felt would be the last major legislative action against Jewish influence in Germany before the matter was left for emigration and demographics to conclude — the expulsion of the Ostjuden, many of whom were actually in the country illegally. Again, rather than being initiated on ideological grounds, the move was a response to external developments. The Polish government in Warsaw, seeking to take advantage of the movement of its Ostjuden to neighboring nations, decided to strip all Polish emigres of their citizenship. The move would render stateless 70,000 Ostjuden residing in Germany, making it even more difficult to deport them than was already the case. In an attempt to beat the clock before the Polish law fell into place, the Gestapo began a hurried operation to arrest and deport 17,000 of these Polish Jews, beginning on October 27, 1938. Although only a fraction of the vast Polish Jewish population was targeted, and “some ended up back in Germany,” the international press bewailed the latest unprovoked “assault on the Jews.”

The media exaggeration would prove fateful. Already seething at the deportation of his parents from Germany, Herschel Grynszpan, a Polish Jew living illegally in France, was further incited by sensationalized accounts that heaped blame exclusively on the German government. Furious, the Jew walked into the German Embassy in Paris and shot dead a young official named Ernst vom Rath. The murder was not the first diplomatic or political casualty of Jewish violence and came just two years after the high-profile murder of Wilhelm Gustloff by David Frankfurter.

Historians have since argued that the German government, and Goebbels in particular, over-reacted to the murder and inaccurately portrayed it as an assault by Jewry against Germany. Cesarani continues in this vein, contending that Goebbels “blew it out of proportion.” However, it is an inarguable fact that both Frankfurter and Grynszpan were acting as Jews, incited by Jewish propaganda, and possessed specifically Jewish grievances. Coupled with physical agitation in the United States, including the boarding of the Bremen mentioned above, the picture that inevitably emerged was one of unified, consistent and violent activity by Jews against the German government. Berlin’s chief of police was therefore not acting unreasonably when he issued an order for all Jews in the city to hand over their firearms, nor was the Gestapo when it reacted to the news by shutting down Jewish newspapers in the German capital. What the government couldn’t do was manage to keep the “high pressure” of the population from briefly boiling over.

The “night of Broken Glass” which is endlessly regurgitated to school children the world over has been wildly exaggerated. On November 9, 1938 damage to Jewish property certainly took place, as did a number of isolated assaults and even deaths. However, as Cesarani concedes, the security police were mobilized almost immediately “to prevent looting,” and the event was remarkably mild when considered among the annals of inter-ethnic violence. The government also severely punished the violence and disorder. As Cesarani notes, “historians know so much about the November pogrom because it was subject to disciplinary hearings by the Nazi Party.” It has long been known that “there were no orders to kill anyone. Nor were there any instructions to wreck Jewish commercial premises.” The events of the night actually “provoked the wrath Göring and Himmler … and resulted in a backlash at home and abroad.” Focussed on encouraging emigration, Heydrich and the SD[i] “despised” the chaos, and Adolf Eichmann was “apoplectic” when he discovered that the Jewish office for emigration had been ransacked. On the afternoon of November 10, the Party broadcast a message issuing “a strict order … to the entire population to desist from all further demonstrations and actions against Jewry, regardless of what type. The definitive response to the Jewish assassination in Paris will be delivered to Jewry via the route of legislation and edicts.”

During the panic and chaos following the murder of vom Rath, thousands of Jews had been arrested and taken to concentration camps, some with the aim of protecting Germans and some with the aim of protecting Jews. Although the arrests were once again the subject of hysterical reporting in the international press, within a few days the vast majority had been released on the personal orders of Heydrich. Around the same time Göring met with business leaders and insurance companies to assess the damage and arrive at a means of moving forward. The Jewish Question was, Göring argued, “essentially an economic question though it would need legal measures to achieve a solution. … The public needed to understand that rioting was no panacea.” At one point Göring cried out with exasperation, “I have had enough of demonstrations!”

The cost of November 9th was exorbitant. Some Jewish businesses may have been damaged, but it was the pay-outs of German insurance companies that hit the German economy hard. When discussion moved to preventing future instances of disorder, it was conceded that foreign Jewish assaults on German diplomats couldn’t be predicted or prevented, leaving the spotlight on the management of relations within Germany. The only viable solution was to continue using legislation to reduce the Jewish presence in Germany, thus reducing inter-ethnic friction.

As a result of a chain reaction of events commencing with Jewish aggression and assassination, the German government introduced a Decree on the Exclusion of the Jews from German Economic Life. In addition to the social clauses of the Decree, the legislation was aimed at decisively encouraging the peaceful, non-violent departure of Jews from Germany. It was the continuation of a policy favoring exodus over expulsion. However, even for legislation aimed at pushing a problematic group to peacefully depart, it was far from all-encompassing.

For a start, over 700,000 mixed-race individuals were exempted from the legislation even if they identified as Jews. Foreign governments protested loudly, mainly at the instigation of their Jewish populations. But there was sufficient awareness of ethnic realities even among these foreign saints, that none were willing to take in the growing number of German Jews now willing to emigrate. The United States, Britain and France feared that any willingness to take Germany’s Jews would be seen as an invitation to other countries like Romania and Hungary to divest themselves of their “Jewish Problem” also, leading to mass Jewish immigration into their countries. Rather than take in these “innocent victims” it was vastly preferable to let mass inter-ethnic tension bubble elsewhere and criticize a host of native populations for not liking it.

At the outset of 1939 Hitler gave a speech to the Reichstag on the state of international politics. He ridiculed the hypocrisy of the democracies for believing sensationalized accounts and for “condemning Germany’s treatment of the Jews while refusing to accept Jewish immigrants.” Jews, he argued, could contribute to a peaceful Europe, but the only way they could do that would be by adapting “to constructive labor elsewhere in the world.” Although much in the speech has been presented in a threatening, negative light, modern scholarship has come to the conclusion that it was actually a “rhetorical gesture designed to put pressure on the international community to expedite the mass emigration of the remaining German and Austrian Jews.” After six years of atrocity propaganda, provocation, and assassination, it was a call on Jews to finally accept the wishes of the German people that they no longer desired co-existence, and a call on the Western democracies to “put up or shut up.”

By this time (early 1939), it does appear that Jewry had given up on maintaining a presence in German territories. Jewish agitation for increased immigration quotas was relentless, particularly in the United States. State Department official J.P. Moffat remarking that “the pressure from Jewish groups all over the country is growing to a point where before long it will begin to react very seriously against their own best interests. … No-one likes to be subjected to pressure of the sort they are exerting.” The French foreign minister, Georges Bonnet even “accused French Jews of sabotaging good relations with Germany by harping on about the suffering of their co-religionists.”

However, Jewish leaders were reluctant to cover the cost of the withdrawal themselves, and resorted to applying pressure to politicians and haggling with governments. Cesarani writes that “Jewish leaders in London and New York looked askance at a scheme that enjoined them to finance the orderly emigration of German Jewry.” They preferred to transfer the cost to non-Jewish taxpayers. In Britain, after the creation of the Reich Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, influential Jews managed to persuade the government to provide £4 million for the re-settlement of Czech Jews in England. U.S. State Department official Robert Pell is reported by Cesarani as writing on May 15, 1939 that: “My candid impression is that our business is becoming a tug of war between the Government and our Jewish financial friends. The Governments are striving hard to shift the major part of the responsibility to Jewish finance and Jewish finance is working equally hard to leave it with the Governments.”

The tug of war took place against a backdrop of tensions in which Germany pressed its rightful claim against the Polish government to the port city of Danzig. Media treatments of the German prerogative were dismissive and hateful, hyping the tension beyond reason. Jewish outlets worked overtime to link Germany’s legitimate territorial demands with its mythologized version of National Socialist Judenpolitik. On September 1, 1939 German troops crossed the border into Poland. Britain and France declared war on Germany.

The efforts of six years of pursuing peaceful Judenpolitik lay in ruins. Taking to the podium of the Reichstag, a shocked but defiant Hitler told Party members: “Our Jewish democratic global enemy has succeeded in placing the English people in a state of war with Germany. … The year 1918 will not be repeated.”

Thus closes the last of Cesarani’s chapters dealing with Judenpolitik. The historians among our readership will of course note there is little factually novel or different about the fare presented here. For example, it’s long been known that the “night of Broken Glass” was preceded by the assassination of Ernst vom Rath. However, what is novel is the subtle yet palpable change occurring in mainstream scholarship in terms of the emphasis it lays on different aspects of what occurred between 1933 and 1939.

To elaborate, there is a significant difference between accounts which state that the assassination offered the National Socialists an opportunity they were practically begging for, and accounts which argue that the assassination actually confirmed the worst fears of the German leadership in terms of Jewish violence, while also providing them with a serious challenge to law and order, economic stability, and international reputation. What Cesarani’s tactical concessions illustrate more than anything is that National Socialist Judenpolitik will increasingly be understood less as the vulgar ideological crusade so many Jewish propagandists have portrayed it as, and more as an ethnically-motivated, complex, even occasionally successful performance of politics.

[1] R. Gerwarth, Hitler’s Hangman: The Life of Heydrich (Yale University Press, 2012), 93.

[2] Ibid, 94.

Review of David Cesarani’s “Final Solution: The Fate of the Jews, 1933–49” — Part Four of Five

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

“It makes no difference what men

think of war, said the judge. War endures. As well ask men what they

think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him.

The ultimate trade awaiting its ultimate practitioner.”

Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian, or The Evening Redness in the West

War and Death, 1939–1949

As I closed my introduction to this review, I noted that the only genuine mystery attached to the Jewish fate during World War II was that there should ever have been anything mysterious attributed to it at all. I may have been a little rash. You see, in more ways than one, “the Holocaust” as a cultural concept has performed one of the greatest vanishing acts in history — the disappearance of the Jews as active participants in a war that certainly took place between 1939 and 1945, but which began long before and continues until the present. Examining the thousands upon thousands of histories of World War II, one would get the impression that there was not only one war, but also only one aggressor. Quite how and why “the Jews” leave the historical stage as belligerents in 1939, when the preceding six years had witnessed them engaging in international propaganda wars, political manoeuvring, and targeted assassinations in several European countries, has been surprisingly overlooked.

Instead of answering genuine mysteries like this, the relevant historiography has been preoccupied by posing pointless questions that have obvious answers. For example, given the German-Jewish relationship prior to 1939, is it really so illogical to conceive that the German armed forces would view Jews as a security threat throughout Europe but especially on the Eastern Front? Further, is it really any wonder that the most common means of dealing with this threat would be the construction of what really amounted to POW camps for Jewish civilians, termed ghettos for the sake of cultural and historical familiarity? Or that rationing in these ghettos would be roughly equivalent to that seen in POW camps? Strangely enough, however, only in the second decade of the twenty-first century are we witnessing the emergence of histories that accept plain realities such as these.

Reflecting a growing scholarly consensus, Cesarani concedes at the start of his exploration of the years 1939–45 that what may have appeared at first glance as anti-Jewish measures during this period were not “necessarily driven by anti-Jewish sentiment.” In 1939 “the German economy had been revved up to breaking point.” As a result, from the beginning of the war effort, the German pursuance of armed conflict was fatally linked to geo-strategic and economic exigencies, and a fanatical concern with security. Food and fuel would always be scarce, meaning that almost every German move in the war was made with a degree of desperation. Germany had only one real chance at victory, and to achieve this victory it would have to overwhelmingly succeed in every tactical advance it undertook. It would also be forced to adopt unsentimental methods in order to secure these victories.

Ruthlessness was a feature of the times. Although the organized elimination of classes of human beings has probably been occurring since the dawn of human history, the French Revolution pioneered the concept in modern times, and the perfection of this danse macabre reached its apogee with the Communists of the Soviet bloc, who led the way in torture and execution squads. Not surprisingly, the desperate and probably over-ambitious Germans formed their own such squads as part of 1939’s Operation Tannenberg, with the purpose of “liquidating” the Polish intelligentsia. Ominous sounding though it was, scholarship has revealed that the German effort was half-hearted by comparison to its Soviet counterparts, and that meetings intended to thrash out its details “were left until the last minute.” Importantly, as Cesarani notes, “Jews were not the target of Operation Tannenberg. … There is no surviving record of any conferences to determine policy on Jewish questions” during this period. Indeed, “rather than treating Jews as a special security threat … [the National Socialist leadership] did not have a clue about how the huge Jewish population should be treated as a whole.”

The situation only altered when Jews began to present themselves as a security threat. Cesarani reports that the first weeks of the war witnessed “the killing of hundreds of ethnic Germans … notably in Bydgoszcz.” Not only did these incidents set an appalling precedent for the future conduct of the war, but they also revealed a curious pattern — most of the towns and villages that witnessed the massacre of ethnic Germans had heavy Jewish populations. Indeed, as one contemporary Wehrmacht Lance Corporal, Paul Rubelt, wrote in a dispatch from the Front, “Jews were for the most part the evil doers in Lwow.”

This leads us neatly to the curious absence from the relevant

historiography of what we might term the “war aims” of Jewry. Rather

obviously, these centred around the defeat of the German nation and the

destruction of the German ethnicity. I don’t attribute any moral

position to this aim, positive or negative. It is simply an historical

fact that it was in Jewish interests for the German military to be

defeated and the German people to be severely punished. Just as the

National Socialist political triumph in 1933 unleashed “high pressure”

in Germany, then Austria, and then in neighboring countries, so too did

the arrival of the Germans unleash “high pressure” in Poland. This

disrupted what had until then been a rather profitable status quo. In

Poland, notes Cesarani, Jews “dominated trade and commerce throughout

the country. … There was a wealthy elite of industrialists, merchants,

bankers, and professionals.” Like their counterparts elsewhere, until

the arrival of the Wehrmacht they had managed to suppress dissent

against this state of affairs for some time.

Wehrmacht soldiers discover massacred ethnic German women and children in Bydgoszcz, 1939

When the levee finally broke, Jewish thoughts were consumed with ambitions for revenge. Cesarani tells the story of one Polish Jew who confided in his diary in the early days of the German invasion “Jews won’t let Hitler get away with it. Our revenge will be terrible.” And, of course, in many places across Poland it was. In retaliation, the death squads formed under Operation Tannenberg undertook the task of grim but militarily necessary reprisals. Jews in turn would up the ante where possible, although from establishment histories of the period we would think that the Jewish population didn’t produce men of fighting age, merely women and children. Histories of actions of the Jewish ethnic group as a whole remain absent from historiography for the period, representing one of the strangest and unaddressed lacunae in the historical discipline.

The focus on German ethnocentrism has of course remained constant, though it is heading in new directions. It is now understood that Hitler was genuinely concerned from the beginning of the war about the fate of ethnic Germans across Eastern Europe, and historians have now reached a consensus that the stereotype of the “land-grabbing madman” must be dispensed with. Carving up Poland after the swift victory, Hitler ceded huge swathes of the Baltic to Stalin in return for the “right to evacuate ethnic Germans and bring them home to the Reich.” For Hitler, blood and soil were intertwined, but blood took precedence. While ethnic Germans looked West for succour, the Jews were unanimous in looking East to the Communist giant.

The carving up of Poland was welcomed by Jews who, as Cesarani states, “looked upon the Bolsheviks as redeeming Messiahs.” One contemporary Jew wrote “When the news reached us that the Bolsheviks were coming closer to Warsaw, our joy was unlimited.” Jewish interests were of course divergent from yet another section of the population – the Poles themselves. Cesarani notes that ‘this was not how the Poles saw it, least of all when the Soviet occupation authorities unleashed their own terror.” Noting the split in interests and war aspirations of the divergent populations of the newly conquered territory, it was Heydrich who advanced the first logical step to maintaining some semblance of stability — the segregation of the populations.