British Politicians Colluded In Murder

Remembering Harold Yates — and the

Corrupt British Politicians Complicit in His Death

11

November 2015

Francis Carr Begbie

Ramleh Cemetery in Israel where Gunner Harold Yates is

buried. NB There are Brits [ New Zealanders ] and Poles too.

Sunday, November 8th, was Remembrance Day, and members of the National Front made their traditional march to the Cenotaph in London as a tribute to Britain’s war dead. As part of the NF’s Forgotten British Heroes Campaign, a special mention was made of a young Sheffield gunner called Harold Yates who was killed in Palestine in 1945, six months after the end of the war in Europe when Jewish terrorists in British uniform attacked a railway junction.

At first glance it seems as if the story of 25-year-old Gunner Yates would scarce merit a footnote. After all, he was only one among hundreds of thousands of others being remembered in similar ceremonies across Britain. But there is an appalling story behind the death of Gunner Yates. For two senior politicians were complicit in the attack that killed him. Tipped-off about the impending assault, they gave it their tacit approval, agreed to turn a blind eye, said nothing and warned no-one.

This is a story of treachery, squalid political expediency and a despicable indifference to the lives of British servicemen. It has not been told in full until now. In 1945 the Palestine Mandate was in the grip of a Jewish insurgency aimed at forcing the British to allow a flood of Jewish immigrants from Europe into the territory. The British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin was determined to resist, as it not only would have been in breach of the undertakings given to the Palestinians by the Balfour Declaration but it would have also meant losing the support of all other Arab countries in the region. To allow this to take place would have meant a war in the Mandate, so Bevin had no option but to maintain a desperate policing action to keep the two sides apart.

But the problem did not end there. The 1945 general election had not only swept Churchill out of office and the Labour Party into power, but among the Labour’s landslide were no less than 46 Jewish MPs. The overwhelming majority of these were not only fanatical Zionists, but they were supported by a loyal auxiliary of non-Jewish MPs at the highest levels of the party, including two men, John Strachey and Richard Crossman, both to become prominent names in post-war Britain. The collusion of these two in an attack that killed a British serviceman is a paradigmatic example of the abasement of non-Jewish politicians who prostitute themselves to Jewish interests.

Both were typical of high-flying Labour ministers at the time and far removed from the English working class they claimed to represent. They both came from well-to-do backgrounds. Strachey was a product of Eton and Oxford. Sophisticated and urbane, he moved in the most politically fashionable circles. In the thirties, this one-time Communist had moved into the Labour Party and had worked hard to ingratiate himself closely with Jewish wealth and political power. When the White working class of the East End of London rose up against Jewish predation under the banner of the British Union of Fascists, Strachey had organised counter-demonstrations with Communist and Jewish street agitators. Working with wealthy Jewish publisher Victor Gollancz and academic Harold Laski, Strachey helped launch the Left Book Club which became an energetic source of anti-German propaganda. He was elected a Labour MP in 1945 and became Under Secretary for Air.

Richard

Crossman attended the highly prestigious and exclusive

Winchester College before obtaining a double-first in

Classics at Oxford. He later worked for the television

magnate Sidney Bernstein, but it was Zionist leader Chaim

Weizmann who most impressed him. Weizmann was a roving

emissary promoting the Jewish cause who was buoyed up by

Lord Rothschild’s generous financial contributions. With

Rothschild’s patronage, Weizmann was able to buy influence

across the globe. Crossman described him as the greatest man

he had ever met.

Richard Crossman’s political career was to rise sharply with his support of Zionism. Crossman said that Jewish state should have been forced on the Arabs by the British at the earliest possible time and that Jewish immigration should have been built up as fast as possible. It was a view he repeated through the pages of the New Statesman which was published by the Jewish founder of the Fabian Society, Sidney Webb. (Crossman was later appointed editor). Crossman became an MP in the 1945 government at the height of the Palestine emergency.

The Jews in Palestine were represented by the Jewish Agency for which the British Board of Jewish Deputies acted as representative in Britain. The Jewish Agency maintained that it had no power over the terrorist gangs operating in Palestine, but this was a deception. In fact, the Haganah was its military wing.

In late 1945 the Jewish Agency decided it had to carry out a terrorist spectacular against British forces in Palestine as a show of strength to its American backers. But worried that this would trigger a brutal clampdown and reprisal from the British, the action had to be carefully measured. The Agency therefore planned one further large-scale operation to paralyse Palestine’s railways.

There the matter might have rested until a remarkable passage was published in Professor Hugh Thomas’s 1973 biography of John Strachey which gave the game away:

Only on Palestine did Strachey have any serious dispute with the government. One day, Crossman, now in the House of Commons, came to see Strachey. The former was devoting his efforts to the Zionist cause. He had heard from his friends in the Jewish Agency that they were contemplating an act of sabotage, not only for its own purpose but to demonstrate to the world their capacities. Should this be done, or should it not? Few would be killed. But would it help the Jews. Crossman asked Strachey for his advice and Strachey, a member of the Defence Committee of the Cabinet, undertook to find out. The next day in the smoking room in the House of Commons Strachey gave his approval to Crossman. The Haganah went ahead and blew up all the bridges over the Jordan. No-one was killed but the British Army in Palestine were cut off from their lines of supply with Jordan.

Incredibly, at a time when the British Army was taking casualties from Jewish terrorist attacks in Palestine, here were two senior Labour members — one a Minister — conspiring to agree to an attack on British soldiers.

But Prof. Thomas was wrong to state that no-one was killed in the attack. The huge Haganah attack is known in Israel as “The Night of the Trains” and took place on the night of October 31, 1945. The railway network was severed in 153 places. Three police launches were sunk and many railway yards and the Haifa oil refinery attacked by Jewish gangs. At one railway junction, 25-year-old Gunner Yates from Sheffield was shot to death. Perhaps he let his guard down by the approaching figures in British officers’ uniforms.

A few days later, the British finally broke the Jewish Agency code, and Crossman and Strachey spent an agitated next few days fearing their role might be discovered. Certainly in the war that had ended just six months earlier, traitors had ended up on the end of a rope for far less.

But in the end it was pressure from the US that forced Britain to allow the Jews into Palestine. In the mid-forties, a bankrupt Britain was dependant on American goodwill for her economic survival through an aid program known as the Marshall Plan. President Truman, as he later explained frankly in his memoirs, was equally dependant on Jewish goodwill for his presidential campaign funds.

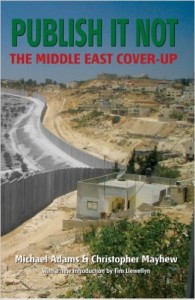

This story might never have come to the light but for the authors of a remarkable book published in 2006 which exposed how Britain’s Labour Party had been captured and exploited by Jewish interests from the earliest days of the 20th century. As noted in Publish It Not — The Story of the Middle East Cover-Up by Michael Adams and Christopher Mayhew (a principal in the affair), “the British government was subjected to ruthless pressure from Washington to get the Arabs to accept the Zionist demands. It was a disgraceful abuse of power.” On one occasion the US Ambassador insisted that the British government comply with the President’s request that Britain admit a hundred thousand Jewish refugees to Palestine “immediately.” Bevin and Christopher Mayhew, his Under-Secretary, objected to what was an obvious recipe for war with the Arabs.

The (US) Ambassador then replied carefully and deliberately that the President wished it to be known that if we could help him over this, it would enable our friends in Washington to get our Marshall Aid appropriation through Congress. In other words we must do as the Zionists wish — or starve. Bevin surrendered — he had to — but he was understandably bitter and angry. He felt it outrageous that the United States, which had no responsibility for law and order in Palestine (and no intention of permitting massive Jewish immigration into the United States), should, from very questionable motives, impose an impossibly burdensome and dangerous task on Britain. (pp. 17–18)

Publish It Not is a remarkable publication not

least because both of the authors were men with impeccable

socialist and anti-racialist credentials. Mayhew was a

Labour minister while Adams was a Middle East correspondent

for the Guardian.

They were outraged at the way in which the Arabs were treated and that Britain’s assurances to them counted for nothing. But equally they were appalled at how Labour, Britain’s main progressive party, seemed to have been, to a large extent, taken over by Jewish influence and money.

Despite their naiveté over the ethnic nature of the conflict, their book has penetrating insights and fascinating information about the perversion of the Labour Party in the twentieth century. Throughout the text they insist on the prophylactic word ‘Zionist’, but it avails them of nothing. In a memorable phrase Mayhew writes:

But a striking feature … has been the relentless way in which those of us who chose to speak up for the Arabs have been harassed by our opponents. They seem not to be satisfied with trying to prove us wrong; they have to prove us wicked as well. Indeed they sometimes showed themselves much less concerned to answer our arguments than to damage our reputations — and they can be surprisingly unscrupulous in the way they go about it.

The capture of the Labour Party by Zionism had been a remarkable phenomenon, wrote Mayhew:

It is a remarkable fact that the Labour Party leaders, though representing a movement which has always vigorously opposed racialism, colonialism, militarism and the acquisition of territory through conquest, never appeared to have made any (recorded) public criticism of Israel at all.

All the more amazing when you compared it with South Africa which practised many of the same policies but which was treated as a pariah. Often it was the same Jewish Labour MPs who led the charge against South Africa who were most active in defence of Israel.

Mayhew was one of the huge Labour intake of MPs who entered parliament in 1945 and soon he was in government office dealing with the fraught question of Palestine. He freely admits that at the time he was new to the Palestine problem and did not understand all the ramifications. At the time it seemed a sideshow. The British Foreign Office was struggling with a number of issues. India and Pakistan had to be given their freedom. The Marshall Aid plan had to be pushed forward. Institutions had to be created for a divided Germany. NATO was about to be formed.

Soon, in addition to an intense whispering campaign, he was being subjected to verbal intimidation, mind games and harassment from increasingly shrill “Zionist” deputations who were demanding more Jewish immigration into Palestine from Europe.

These deputations were always well-informed, articulate, demanding, passionate and ruthless. The most formidable of their spokesman, unquestionably, was Mr Sidney Silverman; he would attack me personally in the most merciless fashion, placing on my shoulders the responsibility for the deaths and suicides of the immigrants whom we had turned back.

On 11 July 1948 a young MP called Christopher Mayhew rose in the House of Commons to speak in an Adjournment Debate about recognition of the state of Israel. The debate had been initiated by an ambitious and energetic backbencher called Harold Lever, and Mr Mayhew was to answer for the government as the Under Secretary at the Foreign Office.

“With an importunity typical of Zionists at that time Mr Lever had started the debate at eight o’clock in the morning after an all-night sitting, and my reply sounds appropriately tired and irritated.” Mr Mayhew pleaded for balance and then said “Has my Honourable Friend ever heard that there is an Arab point of view?”

Thirty years later Mayhew still remembered the scene vividly. While he was accompanied by his sole supporter, his Private Secretary, he faced the massed ranks of the Zionist lobby in parliament on the other side. A group of twenty or thirty pro-Israeli Labour members, most of them Jewish. They included Sydney Silverman, Maurice Edelman and Ian Mikardo. Among them was Israel’s most devoted non-Jewish supporter Richard Crossman.

Mayhew’s boss, the Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin, felt the pressure too as he was constantly being harried by groups of Jewish Labour MPs. At the end of one tense Question Time session he exploded. “We must also remember the Arab side of the case — there are, after all, no Arabs in the House.” This remark provoked uproar and endless accusations of anti-Semitism. But of course there was no counter pressure from the Arabs whose homes, lands and property these Jewish immigrants were seizing. Bevin was passionately anti-Zionist and held that Zionism was basically racism.

Years later an attempt was made to place Mayhew on the pro-Israeli payroll. It happened in 1951 after he had lost his Parliamentary seat and was working as a freelance television journalist. The Director of the World Jewish Congress, Mr A I Easterman summoned him to his office in Cavendish Square, and proposed an informal arrangement. Whenever Mayhew was asked for advice by Mr Easterman, he would be paid “a substantial honorarium” — an obviously corrupt “consulting” arrangement. This was to be a personal arrangement between the two with nothing in writing. “In fairness to Mr Easterman, it should be said that he has denied my version of events.” Easterman claimed he did not make the offer and in any case the World Jewish Congress was a far from wealthy organisation. “All I did say to him about finance was that, naturally, we would re-imburse him for any expenditure that he might incur on our behalf,” Easterman said.

In 1953 Mayhew made his first visit to a Palestine refugee camp and learned first-hand what had been going on. For him, this visit destroyed the myth that in 1948 the refugees had fled voluntarily. This was underlined when the refugees from the 1967 war behaved in the same way and suffered the same fate. They left their homes in panic before the advancing Israeli armies and were then prevented by the Israelis from returning. The pattern was the same in both wars with the exception of the massacre of the village of Deir Yassin.

This was important. Before 1967 the myth that the 1948 refugees had fled voluntarily was almost universally believed in European countries and repeated across the media. During his visit, Mayhew began to feel actively committed to the Palestinian cause. He was shocked by the Israeli leaders’ callous and self-righteous indifference to the suffering of the Palestinian refugees (which they stated to their faces) and he made his views public.

This had consequences for his political career. A senior colleague told Mayhew that frankly it had been his attitude to Israel that counted against him. This was confirmed in an article in Israeli newspaper Maa’riv in 1974.

He wasn’t the only one. One charge that Jewish leadership in Britain has always been sensitive to is that of “dual loyalty” — disloyalty by any other name. Despite the passionate embrace of the cause of Israel by many Jewish Labour MPs, the charge of dual loyalty always left them spitting with indignation.

Andrew Faulds was one Labour MP who did question the matter of dual loyalties. He was not only taken to task by the Prime Minister but deprived of his post as a Front Bench spokesman. In letter to him PM Harold Wilson wrote: “It was because of ‘uncomradely behaviour’… you caused great offence by impugning the patriotism of Jewish Members of Parliament by implying that they had dual loyalties.”

Mayhew notes that while Zionist political contributions to politicians in the United States had always been discussed with admirable frankness (an exaggeration at best), the discretion surrounding such arrangements in Britain meant they were kept confidential.

But one hint as to how things really worked in Britain came in a letter published in a Tel Aviv newspaper in which an Israeli diplomat in the UK defended his embassy against charges that they were not doing enough to sway political opinion. Mr Benad Avital said that he and the Ambassador met personally with 100 supportive British MPs before one debate. “Inevitably, we concentrate on target groups which we consider opinion-making, rather than on every man in the street. This policy has so far paid well” (italics added). As always, the default option for Jews is to pursue a top-down strategy.

Young Harold Yates was far from the last Briton to be killed by terrorists in Palestine in 1945. In the months immediately following VE day, the casualty list included the following colonial police officers: George Wilde, Bertie Sharpley, James Barry, Gordon Hill, Denis Flanagan and Richard Symons.

On December 27, 1945 in an attack on the CID HQ the following officers were killed : Edward Hyde (28), Noel Nicholson (20), George Smith (44) and Privates Likoebe Kurata, Vincent Nthinya, Tapotsa Ntisa all in African Pioneer Corps.

The remains of Harold Yates are interred at Ramleh War Cemetery, Israel, Plot 7, Row C.