This is from Jews and has an amount of factual content. Jews are keen to hide themselves from people which gives this article a degree of interest. Notice that there is a good deal of whining about being victims but nothing about why; that is dealt with by a Deafening Silence. Passing mention of high interest rates gives a clue. The expression we do not hear these days is; in the hands of the Jews. There is no implication of mercy, just extortion.

One who is probably theirs is Jack The Ripper, the notorious murderer. The claim that 50,000 of them served should be regarded with suspicion at best. Look at Oosterbeek War Cemetery and count the number of stars; there are half a dozen at most. There are more men of the Wehrmacht than Jews there. Then go to Jews And War Service for evidence.

Entrance and Persecution (1066-1189)

Massacre at York and Beyond

(1189-94)

Rule of Henry III

and the Barons Wars (1217-1290)

Expulsion of 1290

Readmission

Emancipation

The 1900s

Modern England

Contacts

The Jewish presence in England today is one of the largest in the world. Anglo-Jewry faced increasing persecution from its entrance into England in 1066 until the expulsion of 1290. Once Jews returned in the 16th century, however, they became more and more integrated into society. England was, for a time, one of the most religiously tolerant countries in Europe. British Jewry received formal emancipation in 1858 and has continuously grown larger and stronger.

Entrance and Persecution

(1066-1189)

There were individual Jews living in England in

Roman

and Anglo-Saxon times (80-1066 A.D.), but not an organized community. When

William the Conqueror arrived in England in 1066, he encouraged Jewish merchants

and artisans from northern France to move to England. The Jews came mostly from

France with some from Germany,

Italy

and Spain,

seeking prosperity and a haven from

anti-Semitism.

Serving as special representatives of the king, these Jews worked as

moneylenders and coin dealers. Over the course of a generation, Jews established

communities in London, York, Bristol, Canterbury and other major cities. They

generally lived in segregated areas by themselves. However, until 1177 only one

Jewish cemetery was allowed to be established in London.

During the Middle Ages, usury, or lending money for interest, was considered a sin by the Catholic Church. Therefore, Christians were forbidden to work as moneylenders and Jews were called to that occupation and were able to set high interest rates. They played a vital role in maintaining the British treasury and, for a time, the Crown watched over the Jewish financiers and their property, though they also taxed them onerously. Disputes between Christian clerics and Jews in this period were supposedly encouraged by William Rufus (1087-1100). Another influential English figure was Henry I (1100-1135) who granted the Jews a charter of liberties.

Jews still faced persecution and were not fully protected by the Crown. In 1130, the Jews were fined 2,000 pounds on the charge that a Jew had killed a sick man. The first record of Jews in Oxford is from 1141 when they were caught in the political infighting of two sides warring for the throne. In 1144, the first blood libel charge of ritual murder was brought against the Jews of Norwich. During Passover, the Jews were accused of torturing a Christian child named William, using his blood for the Passover Seder, and eventually killing and burying him. Christians attacked Jewish settlements in retaliation. Despite Pope Innocent IVs protests about the ridiculousness of these allegations, the image of a murderous Jew out to hurt Christians developed in the public mind. These charges were repeated in Gloucester (in 1168), Bury St. Edmunds (1181), Bristol (before 1183) and Winchester (1192).

In 1189, the Third Crusade was launched. The Jews were taxed at a much higher rate than the rest of England to finance this Crusade. Even though Jews comprised less that 0.25% of the English population, they provided 8% of the total income of the royal treasury. Despite the Jews financial contribution, the pro-Christian ideology of the Crusade resulted in rioting in England and some Jewish businesses in London were burned.

Massacre at York and Beyond

(1189-94)

One of the most notorious riots led to the

massacre of the Jews of York. Jews have lived in York since 1170. They felt that

they could use York castle for protection and felt secure among York’s elite

residents, who used enjoyed Jewish financial services. The situation worsened in

July 1189 when King Henry II, a protector of the Jews, died. Richard I was

crowned his heir and he refused to grant Jewish representative admission to

Westminster Abbey, when they came to offer him gifts. Riots were started and

mobs threw stones at the Jews and burned the straw roofs of their houses. Many

Jews were murdered, some allowed themselves to be baptized. Twenty-four hours

later, Richard I found out about the riots and ordered that the Jews be

protected.

As soon as Richard I left to join the Crusade in 1190, riots began again throughout England. In March 1190, a mix of Crusaders, barons indebted to the Jews, those envious of Jewish wealth and clergymen conspired to kill the Jews of York. They burned several houses and approximately 150 Jews fled to the royal castle in York. Led by Richard Malebys, a noble indebted to the Jews, the mob besieged the castle. The Jews had little rations and many killed themselves. On March 16, the citadel was captured and those Jews left alive were murdered. The mob then stole the records of debts to Jews from a nearby cathedral and burned them.

When Richard I returned to England, he was angry at the loss of his chief financial source. He introduced a system of registering in duplicate all debts held by the Jews to safeguard all the taxes he received from them. In 1194, he established the Exchequer of the Jews, a catalogue of all Jewish holdings in England. The Crown could then arbitrarily collect taxes on Jewish revenue. The Jews were forced to respond to this exploitation by charging higher interest rates, thereby increasing their unpopularity with Christian borrowers. Richards successors continued to tax the Jews in every way possible. Payment was forced through imprisonment, property confiscation, torture, and the kidnapping of women and children.

Rule of Henry III and the Barons

Wars (1217-1290)

In 1217, the English Jews were forced to wear

yellow badges in the form of two stone tablets identifying them as Jews. From

the start of Henry III’s reign in 1232, life went downhill for the Jews. By the

mid thirteenth century, more than one third of the circulated coins in England

were controlled by a few hundred Jews, leading the king to levy upon them

untenable rates of taxation and creating rampant anti-Semitism. In 1232, the

king confiscated a newly built London synagogue and in 1253, a decree was issued

forbidding the Jews to live in towns that did not have an established Jewish

community. In 1255, the Jews were once again accused of blood libel. A Christian

boy, Hugh of Lincoln, was chasing a ball when he fell and drowned in a Jewish

cesspool. His body was found 26 days later, when a large Jewish congregation was

gathered in Lincoln for a prominent rabbis wedding. Some Christians speculated

that the boy was killed as part of a ritual ceremony and 100 Jews were executed.

Conditions became so bad in 1255 that Jews volunteered to leave, however their

request was turned down by Henry III who considered the Jews royal property.

During the Barons Wars of 1263, the Jews were seen as instruments of royal oppression and between 1263 and 1266, one Jewish community after another was ransacked and many of its inhabitants killed. In 1265, the Crown started dealing with Italian bankers, minimizing their dependence on the Jews for financial services. In 1269, the Crown further restricted Jewish rights. Jews were not allowed to hold land and Jewish children could not inherit their parents money. When a Jew died, his money reverted to the government. In 1275, Queen Eleanor deported Cambridge’s Jews to nearby Norwich. Also in 1275, Edward I issued the Jewish Affairs Bill, forbidding the Jews of England to loan money on interest. They were allowed to earn a living as tradesmen or farmers, but were ineligible for membership in tradesmen guilds or tenure as a farmer. The Jews became poor and the king could no longer collect taxes from them. In 1278, many were arrested and hanged for secretly continuing their money lending.

Expulsion of 1290

On July 18, 1290, shortly after money lending

was made heretical and illegal in England, Edward I expelled the Jews from

England, making England the first European country to do so. Most Jews fled to

continental Europe, settling mostly in France and Germany, although some managed

to remain in England by hiding their identity and religion. There is

disagreement over the number — either 4,000 or 16,000) — who were actually

forced to leave England. The Jewish exile from England lasted 350 years.

Readmission

The first evidence of Jews in Tudor England

after the expulsion is in 1494. Under Henry VIII and Edward VI, small numbers of

Spanish and Portuguese Conversos (Jewish converts to Christianity) worshiped

secretly as Jews in London and Bristol. Henry VIII used Jewish scholars to

justify his divorce from Catherine of Aragon and his marriage to Anne Boleyn. In

1588, the Converso Dr. Hector Nunes was lauded as a hero for being the first to

warn of the sailing of the Spanish Armada.

In 1589, Christopher Marlowe’s anti-Semitic play, The Jew of Malta, was first performed. In 1594, Queen Elizabeth I’s physician, a Converso named Dr. Roderigo Lopez, was implicated in a plot to assassinate Elizabeth. He was tortured, tried and hanged on what is suspected to be a false charge of treason. Anglo Jewry then fled to the Low Countries, often disguised as Spanish or Portuguese Roman Catholics. William Shakespeare’s famous play about a Jewish moneylender, The Merchant of Venice, was first acted out in 1597. In 1609, Portuguese merchants were expelled from London on suspicion of being Jewish. This did not stop the Jews, however, and in the mid-17th century, a new Converso colony grew in London, made up partly of refugees from Rouen and the Canary Islands.

Historians disagree as to the exact date of the official readmission of Jews to England as well as to whether or not it was Oliver Cromwell who granted it. Cromwell came to power in 1649. Some believe he was influenced to readmit the Jews by Rabbi Menasseh ben Israel of Amsterdam, who functioned as a Jewish ambassador to the gentiles. Menasseh moved to London in September 1655 and on October 31 submitted a seven-point petition to the Council of State calling for the return of Jews to England. He appealed to Cromwell orally at the Whitehall Conference of December 4-18, 1655, which Cromwell had called to discuss Jewish readmission. Cromwell gave no official verdict and when many merchants questioned Cromwell’s ideas he angrily dismissed the conference. Cromwell is believed to have authorized the unofficial readmission of the Jews into England. However, when a few hundred conversos living in England petitioned to establish a synagogue and cemetery in 1656, their request was turned down.

The re-establishment of the Jews in England was a gradual process, one which took many years. Jews immigrated to England from Holland, Spain and Portugal and opened a synagogue in 1657. In 1664, Charles II issued a formal written promise of protection and, in 1674 and 1685, further royal declarations were made confirming that statement. In 1698, the Act for Suppressing Blasphemy granted recognition to the legality of practicing Judaism in England.

The next immigrants were German Jews who started a synagogue in 1690. By then there were about 400 Jews in England. William III knighted the first Jew, Solomon de Medina, on June 23, 1700. In 1701, a Sephardi synagogue at Bevis Marks was opened. A Hebrew printing press started in London in 1705. By 1734, 6,000 Jews lived in England. The Jewish upper class still consisted of brokers and foreign traders, but Jews gradually entered all areas of life. The first Jews were Sephardim, but in 1690 the first Ashkenazi community was formed in London and soon, Ashkenazi established congregations all over England.

Emancipation

In 1753, the Jewish Naturalization Bill (Jew

Bill) was issued to give foreign-born Jews the ability to acquire the privileges

of native Jews, but was rescinded due to anti-Jewish agitation. In 1829, Jews

began arguing for official equality. The first emancipation bill passed the

House of Commons in 1833, but was defeated in the House of Lords. In 1833, the

first Jew was admitted to the Bar and the first Jewish sheriff was appointed in

1835. In 1837, Queen Victoria knighted

Moses Montefiore. In 1841, Isaac Lyon Goldsmid was made baronet, the first

Jew to receive a hereditary title. The first Jewish Lord Mayor of London, Sir

David Salomons took office in 1855. In 1858 came the emancipation of the Jews

and a change in the Christian oath required of all members of Parliament. On

July 26, 1858, the Jewish Baron, Lionel de Rothschild, took his seat in the

House of Commons after an 11-year debate over whether he could take the required

oath. In 1874, Benjamin Disraeli became the first (and only) Jewish Prime

Minister. By 1882, 46,000 Jews lived in England and, by 1890, Jewish

emancipation was complete in every walk of life. Since 1858, Parliament has

never been without Jewish members and recently the Jewish delegation has

exceeded 40 members. A Hebrew Bible, used whenever a Jewish member takes an

oath, sits in the House of Commons treasury box.

In 1841, the first Anglo-Jewish periodical, The Jewish Chronicle, was founded. It still exists today. In 1855, Jews College, a theological seminary, was started. It is now an affiliate of London University that offers rabbinical training and adult education. A Jewish welfare organization for the poor called the Jewish Board of Guardians (now the Jewish Welfare Board) was created in 1859.

In 1863, Rothschild and Isaac Goldsmit of the Ashkenazic community joined Sir Moses Montefiore of the Sephardim to solidify the Board of Deputies of British Jews. Rabbi Nathan Marcus Adler united all Ashkenazic congregations near London into a United Synagogue and created the chief rabbinate of England.

With a renewal of persecution in Russia in 1881, there was mass immigration from Russia to England. The newcomers settled mostly in urban districts. They virtually created a clothing industry in England. They started Yiddish and Hebrew newspapers, fraternal societies and trade unions. The communal leadership encouraged their Anglicization through participation in English classes, state-aided schools and English clubs and youth movements such as the Jewish Lads Brigade. Many became integrated into the community. The Alien Immigration Act of 1905 restricted immigration, but, by 1914, about 250,000 Jews lived in England.

In the early 1900s, Jews became active in both Conservative and Liberal politics. In 1909, Herbert Samuel became the first professing Jew to serve in the British cabinet. He later became high commissioner of Palestine.

The 1900s

The xenophobia created by World War I ended

Jewish immigration to England and caused some British

anti-Semitism.

The war also helped many Jewish entrepreneurs, however, by creating a demand for

uniform clothing. About 50,000 Jews served in the British military, of that,

10,000 died as casualties and 1,596 receiving awards. [ Believe this if you

want. Look at the grave yards in North West Europe and you will see very few;

well under 1% - Editor ]

Zionism began in England with the Hovevei Zion movement in 1887. The English Zionist Federation was formed in 1899. It was England’s Lord Balfour who issued the 1917 declaration officially recognizing Jewish aspirations to a homeland. Israel’s first president, Chaim Weizmann, was also British.

The 1920s were a time of Anglicization of the community. Small Jewish businesses prospered and Jews became professional lawyers, doctors, dentists and accountants. Middle class Jews began joining the upper class at universities and middle class communities sprang up in the suburbs.

The 1930s brought an influx of refugees from Nazism and fascism. Approximately 90,000 Jews came from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Italy and other countries. Many later moved out of Britain and, by 1950, about 40,000-55,000 prewar refugees were left. Smaller numbers came after the war from Eastern Europe, the Middle East and elsewhere. The majority of the Central European immigrants was middle class and brought a large amount of capital to Britain with them. They created or transplanted businesses, especially in fashion trades, pharmaceutical production and light engineering. Other immigrants were professionals, intellectuals and artists. They strengthened both Orthodox and Reform Jewish life.

There was some fascism in England in the 1930s and black shirts led by Sir Oswald Mosley occasionally attacked the Jews. The 1936 Public Order Act helped control violence by banning the wearing of political uniforms. The Jews united to defend against the attacks and also to raise funds to help refugees and to support settlements in Palestine.

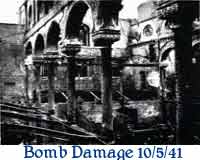

With

the start of

World War II in 1939, mothers and children were evacuated from London. Many

men and women were away from home serving in the armed forces. In 1940, refugees

were subjected to temporary internment. Some Jewish synagogues and institutions

were destroyed in bombings. Jewish life continued in London on a small scale and

new communities were formed in the evacuation areas. The Jewish community of

Oxford, which had remained small since its founding in 1842, grew with

immigrants and evacuees.

With

the start of

World War II in 1939, mothers and children were evacuated from London. Many

men and women were away from home serving in the armed forces. In 1940, refugees

were subjected to temporary internment. Some Jewish synagogues and institutions

were destroyed in bombings. Jewish life continued in London on a small scale and

new communities were formed in the evacuation areas. The Jewish community of

Oxford, which had remained small since its founding in 1842, grew with

immigrants and evacuees.

During the British mandate, Anglo-Jewry was split on the question of a Jewish state. The entire community was against the White Paper of 1939 that limited Jewish immigration to Palestine. The Zionist groups and the World Jewish Congress were for a Jewish state, but the Anglo-Jewish Association was against it. The groups struggled to balance Jewish national ideals with a desire for British citizenship and equality. After the declaration of the State of Israel, the Anglo-Jewish Association adopted a policy of goodwill toward Israel while also stressing the responsibilities of Anglo-Jews to Britain. There was some anti-Semitism in England resulting from conflicts between the mandatory administration and the Israeli settlers, but once diplomatic relations were established between Britain and Israel, normalcy was restored.

An emergency organization had been formed during the war to control the education of children dispersed by evacuations. In 1945, a central council for education in England was founded that represented the United Synagogue and other Orthodox institutions. It reopened three schools that had been closed during the war. One, a secondary school, had 1,500 students.

In the 1950s, many Jews began moving from closed Jewish communities into the suburbs. The United Synagogue started hiring younger rabbis who tended toward religious flexibility. Conflicts arose between different segments of the community.

In some areas, mobilizing support for Israel was a major communal and social activity. Increased involvement and support of Israel took place after the Six-Day War in 1967. Israel’s triumph affected many Anglo-Jews, even those who were not previously committed to Jewish life.

Modern England

The Jewish community has split into different

groups. The largest body is the United Synagogue with more than 35,000 families.

On the right are the Union of Orthodox Hebrew Congregations (founded in 1926 and

dominated by

Hasidic immigrants) and the Federation of Synagogues (founded in 1887 by

Russian-Polish immigrants). On the left are the Reform Synagogues of Great

Britain (1840) and a Union of Liberal and Progressive Synagogues (1902).

The Board of Deputies of British Jews currently has more than 500 members representing synagogues in London and the provinces. It brings together delegates of all shades of religious and political opinion and is considered the governing body of Anglo-Jewry. It is also taken seriously by the British government. For a long time, it mostly acted to protect Jewish political and civil rights. In the 1930s, with the growth of the British Union of Fascists, it fought fascism. In 1965, it was successful in getting incitement to racial hatred considered an indictable offense. Since 1943, it has remained active in matters concerning Israel. It monitors anti-Semitism and works with other groups to safeguard minority rights. It also supports other commonwealth countries.

One of the world’s top institutions for Talmudic learning is the yeshiva at Gateshead. The Conference of European Rabbis is an Orthodox forum that is based in London and is presided over by the British chief rabbi. The Reform movement set up its own rabbinical seminary in 1956, the Leo Baeck College, which attracts students from all over Europe. Significant numbers of Jewish students attend England’s two largest universities Cambridge and Oxford.

The Community Security Trust (CST) is responsible for the Jewish community's security and defense activity, often concentrating on combating anti-Semitism. The United Jewish Israel Appeal and Jewish Care are widely supported among Anglo-Jewry, providing welfare and education to disadvantaged Jews.

Approximately two-thirds of Great Britain’s 350,000 Jews currently live in London. There are large communities in St. Johns Wood (genteel/establishment), Hampstead (intellectual/arty), Golders Green (professional/religious) and Hendon (serious/scholastic). Outside the London borders, suburban communities include Edgware, Stanmore and Ilford, the last of which has the largest Jewish concentration in Europe. Nearby Stamford Hill contains Hasidic groups and immigrants from India, Iran, Yemen and North Africa. Other major Jewish centers are Manchester, with 30,000 Jews, Leeds, with 10,000 Jews, and Glasgow, with 6,500 Jews.

While England's Jewish community has been in decline in recent years due to a low birth rate, intermarriage, and emigration, the 2001 census indicated that there were more Jews than previously thought.

Hampstead is home to Jewish artists, writers and actors. Sigmund Freud’s last house is located at 20 Maresfield Garden in Hampstead. Walking down Hampstead Heath, one passes the homes of various personalities such as Erich Segal, author of Love Story, and the deposed King Constantine of Greece.

Golders Green is the heart of Jewish London with kosher restaurants, bakeries, butchers and supermarkets. Golders Green Road contains Jewish bookstores and gift shops. In the area are dozens of synagogues, temples and shtiebels. Golders Green has the Orthodox Menorah boys school, but most educational institutions are in nearby Hendon. Hendon boasts the Hasmonean and Independent schools, as well as the Jews College and Yakar, a synagogue known for its lecture series.

Finchley is home to the Sternberg Centre, the largest Jewish community center in Europe. It offers Reform religious services, and adult education classes ranging from Jewish walking tours to art classes. The center is also home to the London Museum of Jewish Life, which reflects community life in England since 1656 through documents, photographs and objects. It includes a biblical garden and a Holocaust memorial.

The Board of Jewish Deputies headquarters is in northern London, as are the Jewish Museum, which contains Jewish art and artifacts, and Adler House, seat of the Chief Rabbi and London Bet Din (Jewish court).

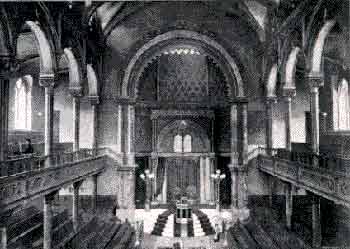

London is home to many old synagogues. The Central Synagogue on Great Portland Street is a modern structure with 26 stained glass windows representing the Jewish holidays. The Marble Arch Synagogue at 32 Great Cumberland Place is the successor to London’s first Ashkenazic congregation (the original building was destroyed by a German bombardment in 1941). West London Synagogue at 34 Upper Berkeley Street is the oldest Reform congregation in London. It has gothic features and a Byzantine-style sanctuary.

In the heart of London, there is still a street called Old Jewry, dating from before the expulsion of 1290. At the corner of Threadneedle and Cornhill is the Royal Exchange with murals by Solomon J. Solomon, once president of the British Royal Society of Artists. The southeast corner of the exchange was once known as Jews walk. Nearby, on St. Mary Axe, is Bevis Marks, the Spanish and Portuguese synagogue finished in 1701. The Cunard Building on Creechurch Lane marks the site of the first synagogue built after Cromwell’s resettlement of the Jews in 1657. Many businesses in the East End are still Jewish owned and cemeteries, former synagogues, and open-air markets remain. The former synagogue at 19 Princelet Street is being converted into a museum of immigrant history.

Many British museums have exhibits of Jewish interest. The British Museum on Great Russell Street contains an Ancient Palestine Room. Their manuscript department holds the original Balfour Declaration. The National Gallery has several of Rembrandt’s paintings of Jewish characters. The National Portrait Gallery has images of Jews from Moses Montefiore to Israel Zangwill. The Victoria and Albert Museum contains various ancient Jewish artifacts. A new Holocaust exhibit, which contains rare items from former concentration and extermination camps, has also recently opened at the Imperial War Museum.

Ramsgate, near London, is the site of the Montefiore estate where Moses Montefiore lived. The site contains his private mansion and a synagogue that he built. The Montefiores are buried on estate grounds.

Further from London is York, containing Clifford’s Tower the site of the York massacre of 1190. A memorial stone sits at the site.

England’s educational centers, Oxford and Cambridge, both have strong Christian influences, but there are some Jewish sites. The Oxford synagogue, at 21 Richmond Road, is at the site of the original synagogue built in the 1880s. The building was redone in the 1970s, although one wall of the old building still remains. The synagogue has both Orthodox and Reform services.

St. Aldate’s street was once the center of the Jewish area in Oxford. Three of its houses - Moyses, Lombards and Jacobs Hall, are thought to have been Jewish homes. At the Botanical Garden opposite Magdalen College, a plaque commemorates the site of the old Jewish cemetery.

The Bodleian Library in Oxford contains 3,000 Hebrew manuscripts and 30,000 volumes in Hebrew. It also displays a bronze alms bowl that belonged to Rabbi Yehiel of Paris in the 13th century. In the Draper Gallery of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum is a collection of antiquities excavated in Jerusalem.

Cambridge’s synagogue is located at Ellis Court. During the school year, students run its services and kosher kitchen. One of Cambridge’s oldest colleges, Peterhouse, stands on land once owned by a Jew. The old Jewish community had two centers. One was within the triangle made by St. Johns Street, All Souls Passage and Bridge Street, while the other was a marketplace where Guild Hall now stands.

The Cambridge University Library has a myriad of Hebrew books including the Schechter-Taylor Geniza Collection numbering tens of thousands of items. Trinity College and Girton College also have Judaica collections.

In 1231, the Earl of Leicester barred Jews from taking up residence in the city and forced landlords to pledge to keep them out. It was not until January 2001 that the Leicester City Council formally renounced the nearly 800-year-old ban on Jews (JTA, January 18, 2001).

The Jewish Chronicle, the Jewish Telegraph, and The Jewish News all report on Jewish communal affairs and serve the northern cities. www.totallyjewish.com and www.somethingjewish.co.uk are UK based websites that carry national and international news.

In 2003, the Jewish Leadership Council was formed, bringing together heads of major national Jewish organizations and key communal leaders in an effort to encourage communal organizations and leaders to be in greater contact so they may better represent the community.

Nottingham Hebrew Congregation

Shakespeare Villas

Nottingham NG1 4FQ

Tel. 0115-9472004

Email. OfficeNHC@aol.com

Web. www.nottshul.co.uk

Marjorie & Arnold Ziff Community Centre

311 Stonegate Road,

Leeds, LS17 6AZ

Tel: 0113 218 5888

Fax: 0113 203 4915

Web. http://www.mazcc.co.uk/

Sources: Barnavi, Eli.

A Historical Atlas of the Jewish People. New York: Alfred A. Knopf,

1992, pp.140-141.

Encyclopedia Judaica. England. Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House,

1971.

De Lange, Nicholas. Atlas of the Jewish World. New York: Facts on File,

1984, pp.168-171.

Shamir, Ilana and Shlomo Shavit. Encyclopedia of Jewish History. New

York: Facts on File, 1986, p.78.

Smith, Goldwin. A History of England. New York: Charles Scribners Sons,

1957, p.97.

Stirling, Grant.

The History of Jews in England. 1998.

Tigay, Alan.

The Jewish Traveler. Hadassah Magazine, 1994.

Bulkacz, Vanessa. “Despite

Comcerns About Safety, British Jews to Celebrate 350 Years.” JTA. August 22.

The Stephen Roth Institute for the Study of Contemporary Anti-Semitism and

Racism, Annual Report 2005,

England.

Photo Credits: Ilford synagogue photo courtesy of

Ilford Synagogue.

Central Synagogue photos courtesy of the

Central Synagogue.

New West End Synagogue photo courtesy of the

New West End Synagogue